Help to save 50 new homes for homeless people!

/Help save 50 new homes for homeless people in Camden – tell the Government this unloved building should not be listed.

Read MoreHelp save 50 new homes for homeless people in Camden – tell the Government this unloved building should not be listed.

Read More(Updated 9th August 2020)

Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick’s new White Paper on Planning for the Future has three main ideas. First, that the planning system is slow and inefficient. He aims to make it faster by simplifying it and moving it online using open standards and data.

Second, to address shortages of housing that make UK homes twice as expensive as in Italy, Germany or the Netherlands, he will set councils harder and higher requirements for new housing in expensive areas, especially in and around cities.

Third, he accepts recommendations of the late Sir Roger Scruton’s Building Better Building Beautiful Commission, to ensure new buildings are more beautiful and more human, by requiring the creation of design codes that new development ‘should’ conform with.

The real teeth are in the new, higher, binding housing requirement of 300,000 new homes per year, focused on expensive and particularly urban areas. The Government will adjust those targets to allow for green belt and other protected land, but will expect councils to allow better use of low density brownfield land. It will also remove the current cap on what the targets can be. That all means some councils, particularly in the South East, will face much higher housing targets.

He aims to give more certainty after local plans have been written, by ‘bringing the democracy forward‘ into the creation of plans rather than during the application for permission. This part of the White Paper has been controversial. But in fact it is unlikely to harm residents much, because any land allocated for development under an existing local plan is already virtually certain to get planning permission on appeal eventually, even if the council initially turns it down. To achieve that, he will replace the entire corpus of plan making law in England. He will also strengthen planning enforcement.

Legalistic ‘evidence bases’ will be replaced with a council’s statement of reasons. The inspector can approve the plan with the reasons given by the council or amend it as requested by third parties, using their reasons.* Councils considered at ‘higher risk’ of missing the new time limit of 30 for writing their plan (with an extra year if they already have one adopted or submitted) will get mandatory visits from the planning inspectorate. If they miss the deadline, the Government can step in directly and write its own plan, in consultation with local people. Local authorities ‘could’ prepare design codes at the same time as writing their plans, or afterwards.

New local plans will become a map divided into three types of zone, and a key specifying the permitted uses for each site. New allocations of greenfield sites for housing will become ‘growth’ zones suitable for substantial development, where outline planning permission is granted by the local plan itself. Masterplanning can either be done by the council at plan stage or as a planning condition. Development management policies will mainly be moved from local plans into national policy. (Does this mean Mayfair will have the same rules about noise and mitigation as rural Yorkshire?) Environmental assessments will become more efficient, so they are considered up front and with open data.

Unlike the zoning system in other countries, which are so precise that they are unambiguous, these proposals seem to keep some discretion at later stages as councils decide on more technical aspects of the development. How exactly that will work is still to be announced.

In existing settlements where some development is desirable, to be labelled as ‘renewal’ areas on the local plan, he proposes a strengthened presumption in favour of development for the uses specified in the local plan for that area. Under the fast track to beauty, if a building complies with a design code and other requirements, there will be an automatic planning permission or permitted development right.

The design codes are to be ‘more binding’ (than what?), whereas the new requirement for housing numbers will be ‘binding’; is there a difference? Local authorities will still be allowed to grant approval for developments that do not comply with the local plan, although it may be tougher. Permitted development will apparently be extended further, subject to the new design codes and could also be made subject to the new developer levy, to remove the current loophole. There will be nationally set standards and codes, as well as locally set standards and codes.

In conservation areas and other ‘protected’ areas, the current system remains essentially unchanged. He will facilitate enhancing historic buildings and making them more energy efficient, perhaps by allowing experienced conservation architects to determine that listed building consent is not required for routine matters – as is technically the law now if the historic character of the building is unaffected, although the risk of criminal penalties has a chilling effect.

There will be even more teeth if he adopts the idea he floats of deemed permission when authorities fail to decide a planning application in time. Planning applications will be made simpler, with more delegation to officers if the planning application complies with the local plan.

The Government aims to simplify the current system of levies on developers and replace it with a single flat rate percentage infrastructure levy on land value, paid when the homes are occupied. That will remove the current lengthy process of negotiation. With a single national rate, the percentage rate levied will fall in some high cost areas, but the Government claims that the overall amount raised should increase, presumably through more being built in more expensive places under the new targets. But the ‘section 106’ agreements that he intends to replace are also used for things like new rights of way, which cannot efficiently be replaced with a cash sum. Hopefully that will be saved.

Councils will be able to borrow against the new levy and use it for infrastructure, social housing, and general purposes. It promises to ensure that affordable housing provision supported through developer contributions is kept at least at current levels and that it is still delivered on site. How it will do that remains to be seen.

There is also a suggestion that landowners who want their sites to be included for growth or renewal in the local plan should pay a fee to the council, to help fund creation of the new local plan.

The Government wants to expand the use of Development Consent Orders for new towns and other large sites, and to look at reforming Development Corporations. Some think that may be very significant.

Mr Jenrick will also make it easier to write neighbourhood plans, which will still have their current power to set design codes. Design codes can take a lot of work: under current law they require a technical ‘evidence base’ that can be costly and lengthy to write. His intention to reduce the current legalistic requirements for evidence bases for plans and design codes will help make things easier. In addition, he will set up a new body to support the delivery of ‘provably locally popular’ design codes.

There is a hint of a new process for addressing neighbour concerns after permission in principle has been granted. Will this involve neighbour consents like a scheme in New Zealand, or lack of objection as the Government has suggested before?

An accompanying consultation also asks about more transparency for options over land, which are often not publicly disclosed. They should be careful not to encourage existing owners to hold out for higher prices, which would prevent plot assembly by someone trying to regenerate a dilapidated area. Ebenezer Howard’s schemes would have been impossible if he had to tell the selling landowners he was collecting land for a new garden city.

The obvious first step to make land data more available is to remove the fee for land registry data. Private databases have already collected it all; there is no good reason not to make it available to everyone. It is a public good. The land registry office already makes it available for a fee, so there can be no privacy issues.

If you want more detail on all of the above, this video with Chris Katkowski QC is very helpful, as is this summary by Zack Simons.

There are many good things in the White Paper. No one with any sense can object to making the planning system more efficient. Beauty and better design will no doubt help overcome the political obstacles to more housing, as will better developer contributions to address the negative effects of new developments. In proposing harder, higher, more focused numerical housing requirements, the White Paper is implicitly recognizing that efficiency, beauty, and better mitigation will not be enough on their own to deliver the many homes we need.

Unlike all our other rules about land use, the planning system was never designed to find win-win solutions that would address spillover effects on other people. There is enormous scope to build well, ensuring plentiful affordable housing, while making the local community happier – solving the political obstacles to even more ambitious reform.

The White Paper expresses interest in achieving that, by giving single streets of residents the power to allow more development of forms that they are happy to see. That should unlock a growing tide of graceful urban intensification and new homes as residents of ugly bungalows or semi-detached houses realize they could retire if they gave themselves permission to build beautiful terraces or mansion blocks instead. It would be an easy way to get popular design codes and local support in the new ‘renewal’ zones, while enabling more people to walk, cycle and use public transport.

We will only have plentiful, high quality, affordable housing when building new homes is truly popular with the locals. To achieve the two percentage point boost to annual GDP growth that eminent economic historian Nicolas Crafts says better planning would deliver, we would need to go further than this White Paper and adopt bottom-up processes to unleash a popular wave of new building. But this is an ambitious step in what – depending critically on the details and implementation – seems to be generally the right direction.

—

* Local plans will be tested against a new single sustainable development test, replacing the ‘soundess’ test and sustainability appraisals. The housing requirement will look at outcomes rather than process: the five year housing supply test will go and be replaced by an annual check on how many homes were actually delivered in the previous five years. The presumption in favour of allowing new development as the penalty when targets are not met will remain.

Given current headlines about certain controversial planning decisions, the Planning for the Future report on the problems with our discretionary system could not be more timely. With a pandemic and continued severe housing shortage in many places, we desperately need to boost growth and level up different parts of the country.

Anthony’s report sets out the many disastrous effects of the housing shortage caused by our failure to build or plan well – not least inequality, speculation, and bad, unaffordable homes. He explains that land banking is a symptom, not a fundamental cause, of our problems, and that contrary to our intuitions, it would be better to have more vacant homes, not fewer.

He examines why clear, predictable rules are crucial to lower the costs of development and make homes more affordable. He calls for much more land to be made available for housing, and joins others in recommending that plans should have clear and unambiguous rules. We should frontload the hard questions with the public when writing the plan, like the French, Japanese and many other systems: then anyone can quickly know exactly what they can build, by consulting a clear and precise code.

Anthony boldly calls to replace the Green Belt by phasing non-developed land into the zoned area, depending on local population growth: subject to conditions ‘[d]evelopers in growing cities who come forward with unzoned, greenfield large sites that can provide significant amounts of additional housing legally must have their land added to the zoned area.’ The report suggests simplifying developer contributions with a new flat-rate 20% levy on the value of development.

This all raises many interesting questions, not least the oldest and hardest in planning reform: how, in the cold hard world of real life politics, do we get there from here? How would we actually implement it?

It is easy to envisage a zoning code for new greenfield or large brownfield sites. But what about urban intensification, where the existing buildings and spillover effects often vary drastically between plots?

Councils have powers to do a kind of zoning now, through Local Development Orders, but rarely do. Many would prefer to avoid controversy by picking zoning rules like parts of the US, where the building envelope permitted by the zoning rules is smaller than the existing buildings, so nothing more can be built. If ‘most ordinary neighbourhoods [are required to] allow slightly denser housing than their existing form’ as the report recommends, that is effectively a supercharged new permitted development right. That might be a bit controversial.

Another question: who will decide on conservation and other special areas? How will his suggested ‘economic cost-benefit analysis’ value the existing heritage and amenities? The Roskill Commission famously fluffed that question.

And if development will still be constrained at all by zoning, which will still be set by discretion, might it still suffer from the Kornai critique that Anthony eloquently explains?

It would be brilliant to see a follow-up report addressing those questions in more detail.

One way to get to zoning and more homes might be our suggestion, which Centre for Cities and many others have already recommended for trial: let residents of each single street (or each city block) decide by a two-thirds majority to adopt a design code and allow more housing on their street or block, subject to limits to protect others.

Those new rules for that street or block would be a form of ‘zoning’. It would spread organically as more homeowners see the benefits of giving themselves permission to do more with their plots – hopefully in some cases choosing to replace, say, suburban semi-detached houses with mansion blocks holding five times as much housing per acre.

Similarly, many parishes would be happy to permit some more good homes in their own green belt, but are blocked by planning rules. That is another potentially easy way to get to zoning.

If building more homes would be more ‘efficient’, in the technical meaning of economists, then by definition in some places you could design the new housing well enough, and share enough of the benefits with locals, for a majority of them to support it. (Otherwise, the housing shortage is unfair, but not technically inefficient.) If so, lowering what economists call ‘transaction costs’ by making it easier for people to negotiate win-win solutions might lead to much more housing of the right kinds in the right places. It must be worth a try.

Planning reform has a trilemma. Fast; big; no house price crash: choose two. If you really want to fix things once and for all, perhaps you need to start soft and slowly build irresistible force, like a heavy snowfall.

You might call the report’s approach ‘policy analysis’, ‘institutional economics’, ‘applied political economy’ or ‘systems thinking’. I hope a sequel will use the same approach to give detailed, shovel-ready reforms. For too long, systemic thinking has been in even shorter supply than the homes themselves.

This post first appeared on the Centre for Cities website.

Ian Mulheirn, an analyst who argues that there is no shortage of homes, has written a new post citing a recent estimate that if we had doubled the responsiveness of our housing production – to still below the underwhelming levels of Canada, Japan and Denmark – prices would only be about 9% lower than they are today.

There are three reasons why that does nothing to rebut arguments for building more homes.

First, all the 9% estimate tells us is that double nearly nothing is still not very much. As the paper he cites explains: “[doubling] the stock elasticity of UK housing supply […] would be consistent with (but still short of) the underlying flow elasticities of Canada, Japan and Denmark (yet remains considerably smaller than the US)”. And yet economists across the US are screaming for better housing supply.

It also raises the question of where you would build those homes. Some parts of the UK – sadly with few good jobs, and perhaps with fewer wealthy residents to get upset about every inconvenience from nearby construction — are much better at building homes than, say, Oxford or London.

Mulheirn’s own estimates of the effect on prices of building more homes tell us that if we build enough, prices would not rise. They also let us estimate how many homes we would need to build. And this graph from the housing analyst Neal Hudson shows that in the past, we have often grown the housing stock much faster than we do today.

Mulheirn has never given any plausible reason why we couldn’t get back to historic rates of growth in the housing stock. Certainly technology is far more advanced than it was during the previous booms in the 1820s or 1930s. In the 1920s, cars cost the same as a house. New homes in parts of the US are vastly cheaper than here. The only thing missing is a better planning system that can get more homes built where they are most desperately needed – within reach of good job opportunities.

Mulheirn also has “a” and “the” mixed up. Of course interest rates have been “a” cause of rapid house price growth, but not “the overwhelming cause”, as he claims : lack of supply has been a cause too. Cities like Atlanta and Houston that build plenty of homes have not seen a substantial increase in house prices above the cost of building them.

The gap between the price of homes and the cost of building new homes is critical, because it illustrates the ‘wedge’ created by poor planning resulting in needlessly low supply. In much of the South East, the wedge accounts for over half of the price of a home. That wedge does not occur in places with healthy supply. Mulheirn does not address the evidence of this wedge.

Second, he argues that building more would just result in more empty homes. But all of the evidence points to the contrary: absent a dysfunctional planning system, high prices in places within reach of good opportunities, where people most want to live, would cause most new building to happen in those areas. Something like half of the family homes in London are occupied by unrelated people sharing. Why on earth would all the new homes stay empty, when the London vacancy rate is lower than many other cities in the UK and elsewhere, and lower than it has been in decades past, there is a long line of people keen to live on their own, and when the homes we already build are not all empty?

Third, Mulheirn points out that the original Bank of England paper’s finding that prices could have risen by about half as much under conditions present in a selection of other OECD countries is largely driven by smaller reductions in government bond yields in those countries, not by differences in supply elasticities. But it is unrealistic to assume that more building would have left UK bond yields unchanged. Under a better supply scenario, where housebuilding increased significantly, competition for financing for the capital-intensive task of building homes would drive market interest rates higher.

The strongest part of Mulheirn’s article is where he notes the risks to first time buyers if interest rates were to rise. That is a major reason why economists argue for a much healthier supply of homes over the long term. Studies show that will mitigate or prevent house price increases, and substantially reduce the boom-and-bust cycle that he purports to worry about. Houses should be priced more like furniture. Build well, and they may hold their value. An exceptional work, well cared for, may even go up in price. But it is unjust and unhealthy for the prices of basic necessities to rise far above the cost of providing them.

This article first appeared in CapX.

John Myers spoke at the Raising the Roof debate at the IEA on 31st July 2019, with Luke Murphy of IPPR, Mairead Carroll of London First and Dr Radomir Tylecote of the IEA.

Thank you very much for the invitation to speak.

London YIMBY is a non-partisan campaign to end the housing crisis with the support of local people.

We're not interested in magical thinking. We're not interested in ideas that have been pushed for fifty years but no politician in power will ever be brave enough to do. When homeowners are two thirds of voters, good luck with a reform that annoys nearly all of them.

We're just interested in what might work.

To try to find that we went through literally over a thousand reform ideas, all of which politicians have found too controversial, until we finally found two that we thought could be both popular and effective.

One of them on green belt was partly adopted last year, less than a year after we published it, so I’m going to talk about the other. We call it Better Streets and Radomir has very kindly included it in this IEA report.

When you think of, say, London you probably think of places like Soho, Covent Garden or Bloomsbury. So do all the tourists – that's what they travel round the world to see.

But those beautiful popular historic areas have literally five to ten times the built cubic volume per acre of most of the vast two storey suburban sprawl of Outer London.

Most of Outer London or Cambridge is 1930s two-storey semi-detached houses or similar, often with front gardens concreted over for parking. In London, much of it is within walking distance of a station.

They're perfectly decent houses. They were built for the working classes to buy in the 1930s – at three times average income by the way – but we could make much better use of that land now with taller terraced houses or mansion blocks, of five or six storeys. Even the Elizabethans built to six storeys. Perhaps we could dare to match them.

Just getting planning permission to do that allows you to literally increase the housing on a plot by a factor of five, often making the original street look better if you have the right design. The planning permission is so precious that it will often double the value of the original house, which homeowners tend to like.

In those areas, there is scope to add literally millions more homes over time with contributions from the developers for infrastructure and other important things.

The trick is how to do it without hundreds of thousands of people screaming about overshadowing, noise, congestion and parking, which is why you can’t get permission to do that today.

So our idea is to let residents on each street choose, if they want to, to set a design code for terraced houses or mansion blocks on their street and vote requiring a two-thirds majority to give themselves each permission to add much more housing on their own land.

They're not forced to use it. It's just a permission. They can sit on it, or sell the house with the permission to a small builder, or team up with some neighbours and a developer. Homeowners generally love the idea, because it turns out that a colossal amount of free money is quite popular.

You need to set maximum heights and other rules to protect the neighbours, of course, but that's not too hard. It's a win-win solution that, over time, can get millions more homes built in the places like London or Cambridge with the best job opportunities and the worst housing crisis. We have more detail on our London YIMBY website if you are interested. Thank you very much for listening.

We have just submitted our suggestions to the Labour Planning Commission. You can read the full document here.

We summarized the evidence for the Smith Institute’s Affordable Housing Commission. You can read our submission here.

John spoke at the 2019 Creating Communities conference

Read MoreFirst published in CapX and reproduced with permission.

Why can’t you afford a home?

UCL researcher Josh Ryan-Collins says it is due to inevitable landowner profits from land, to a majority of homeowners blocking fair taxation of those profits, and to excessive mortgage credit. His new book is not yet widely available, but he has written a long summary.

Causation is complex. Lawyers speak of ‘but-for’ causes; economists of ‘counterfactuals’. Things often have many causes, which can be necessary or sufficient in different combinations.

Ryan-Collins rightly asks questions about the banking system. For centuries, banks have received various implicit subsidies – too-big-to-fail status, deposit guarantees, lender of last resort facilities, exclusive access to reserve accounts, and maturity mismatches illegal in any other retail financial service – at a value and opportunity cost to the taxpayer of many trillions and without any serious check that we are getting value for money.

And it is certainly true that banks did far less mortgage lending in prior centuries. The peer-to-peer UK mortgage lending of the 1800s has been almost entirely forgotten.

He is right that easy bank financing and low nominal interest rates have driven up the price of housing, at least in some places. But, crucially, not in the places with a healthy supply.

A 2018 study by Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko showed a striking difference between two groups of cities. In cities like Atlanta, more demand and low interest rates were met with a jump in building new homes, while prices barely moved. In cities like San Francisco, the flow of new homes barely budged while prices vaulted.

In Cuba, cars are ‘unique’ and fixed in quantity because imports are prohibited. Second hand cars there rise in price, just like UK housing.

He is also right that private home ownership makes the politics of fixing housing far harder. Homeowners are happier when their house price goes up. Hence the tyranny of the majority, and the current explicit UK government target for house prices to continue to rise.

The 1950s upturn in his graph of global house prices coincides quite well with homeowners becoming majorities. Of course, it also correlates rather well with the introduction in 1947 of a ‘modern’ UK planning system without serious testing or any intention to facilitate large-scale densification of existing cities.

But his argument does not explain the experience of the UK in the 1930s, for example, when interest rates were low, de facto 100% mortgages became available and yet the working class were suddenly able to afford to buy homes in London because the Tube system enabled housing on land that used to be too far out. Meanwhile, landowners desperate to find something to do with their central London properties turned them into highly affordable mansion blocks with vastly more homes per acre, to tempt the middle classes.

There are crucial aspects of the microeconomics of housing that he glosses over.

If you are lucky enough to own a home in the south-east of the UK, the most expensive element is probably not the cost of building it. It is certainly not the land. It is probably the planning permission for that home to exist.

Land in the UK, even in the south-east, is surprisingly cheap if you eliminate the possibility of building on it – somewhere around £10,000 per acre.

You can test this in real life by knocking down a building, getting it designated as Metropolitan Open Land or green belt so that it can never be built on, and asking a surveyor to value the land for you. Or you can read the careful statistical studies that clever spatial economists such as Paul Cheshire, Christian Hilber, Ed Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko have done. (You will find that cheaper, if perhaps not easier.) Or ask a land promoter or planning consultant what they do all day and why.

Land is not, as Dr Ryan-Collins claims, unusual in economic terms in that it exists in a fixed quantity. So do aluminium, hydrogen, sunlight, seawater, and the number of hours someone can work per day.

Plenty of things exist in fixed quantities. They are examples of what economists call ‘inputs’. The story of the industrial revolution is of a vast increase in standards of living as we have learned to do far more with various inputs – for example, energy and even the weight of materials required for a product. For that reason, many products and inputs are far more affordable than they were.

Land does not inevitably appreciate in value over time. Agricultural land is far more affordable than in earlier centuries, because we have learned to produce more with it and to make better use of farmland in different places.

Land for housing is important not because of soil but because of location. A city of floating houseboats would experience many of the challenges of today’s land-based cities. So would a thirty mile high skyscraper on a small plot, or a future city in orbit. In some places it would be economic to live suspended from a helium balloon tethered above existing homes if you were allowed to. The hard thing is getting the permission.

Land supply may be inelastic, as he says – though not entirely, if you are Dutch – but land is only an input. We have a shortage of housing, not land, and housing supply is highly elastic in many places because, as with so many other things since prehistory, we have invented technologies to do more with a limited input: to add more homes on a particular piece of land. You know those technologies as staircases, chimneys, terraced houses, mansion blocks and lifts. Or you can look at them as creating more layers of land on top of one another, all in the same place on the map.

We have also invented technologies to substitute one piece of land for another. We call those bicycles, buses, cars, trains and videoconferencing. You cannot move land, but you can move people, or reduce the need for them to live near each other.

Some of the prettiest and most popular parts of many UK cities have literally ten times more housing per acre than much of the rest. We have vastly more scope to add more homes on existing land if we want to. There is no shortage of land at all. You could double the amount of housing, and double it again, and still have a prettier, fairer city. Do you really think homes would still be so expensive if we had four times as many? They would be affordable long before that.

To enable better outcomes, we need a better planning system.

He is right that planning systems did not suddenly become much more restrictive at the turn of the century. Tokyo actually allowed much more housing – which is why Tokyo became more affordable. But if you fix the total amount of housing allowed as many places effectively did a long time ago – and Los Angeles and Manhattan have actually reduced it – then housebuilding will increasingly bump up against that limit. Planning became more of a constraint over time, as Prof. Cheshire would put it.

If you want houses to be treated more like furniture, not speculative assets, then the obvious answer is to let people build many more of them, so the price does not rise inexorably. There is no speculative bubble in sofas.

People are not fools. Many want to own housing because prices have trended upwards for their whole lives.

It is not ‘remarkable that house price-to-income ratios have been moving in the opposite direction in Western democracies and mature East Asian economies such as Korea, Japan and Singapore,’ as he claims. Those places have been building many more homes per head where it matters, as the GLA’s Housing in London 2018 report shows:

The people who publish regression analyses in high-quality peer-reviewed econometrics journals are unanimous that a better planning system would vastly increase the supply of homes and make them far more affordable.

How long can some ignore their evidence? Centuries probably. That’s why our campaign focuses on working with those with open minds to get real progress. Within twelve months after our first report, the core of one of our two main requests is now national planning policy.

The real question about housing, as he implicitly acknowledges, is what to do about it.

His call for political leaders to be brave is, sadly, exactly what housing campaigners have been asking for decades. It may excite your political base, but it will not help those in need, nor solve the feedback loop that keeps homeownership percentages high and entrenches political opposition to change. Political scientists have plenty of answers about how to achieve change, if you only ask them.

There is every reason to support sensible tax reforms. But most of the US has far higher annual property taxes on homes than the UK, and yet the US still has problems. Good luck imposing swingeing taxes not matched to cash flows on a homeowner majority. Even if you did, most people would still have less housing than they would like. Sensible tax reform will not end the shortage of housing, any more than taxing water in a drought.

And good luck weaning people off owning homes, as he suggests, without a credible promise that homes will stop getting more expensive.

No doubt we should look carefully at the banking system. But no change to that would ensure housing that is affordable as it could be.

Sadly, the final reason ‘why you can’t afford a home’ that he omits is that too many housing campaigners insist on their way or the highway. We would be far more powerful as a united coalition pushing for all the changes that would make a difference. Why not try to pull every lever we can?

We need to stop pretending that we have a shortage of land or that any of this is inevitable.

There are easy ways to improve the planning system that would lead to vastly better places and more homes over time. We could even do it without touching any pleasant greenfield sites, given a sufficient alliance to push through the right changes.

To deny the overwhelming evidence of the good that would come from a better system is to betray those most in need of help. We should work together to give people fair life chances, and plenty of truly affordable and beautiful homes.

John Myers is co-founder of London YIMBY, a grassroots campaign to end the housing crisis with the support of local people.

John published a new piece in CapX:

Horrified passengers suddenly realize their boat has a leak. They frantically start to paddle it with their hands towards a distant shore. The engine and sail sit ignored and unused. Meanwhile, someone at the stern refuses to raise the anchor.

Theresa May’s announcement of new housing policies today has something of that feel. No-one can doubt her government’s determination to do something. She is bang on target when she says:

The shortage of housing in this country reinforces inequality. It prevents social mobility and stops people fulfilling their potential. It creates and exacerbates divisions between generations and between those who own property and those who do not.

Read more here.

Last chance to support more homes in the draft London Plan

Read MoreIn Santa’s hideaway at the North Pole, there are a thousand large, equal plots of land and a thousand elf families...

Read MoreWith PricedOut, we sent a response to the TCPA’s Raynsford Review consultation, calling for urgent action on the housing crisis.

Please let us know what you think!

We have been really pleased by the reactions so far, summarized here.

Please let us know your thoughts!

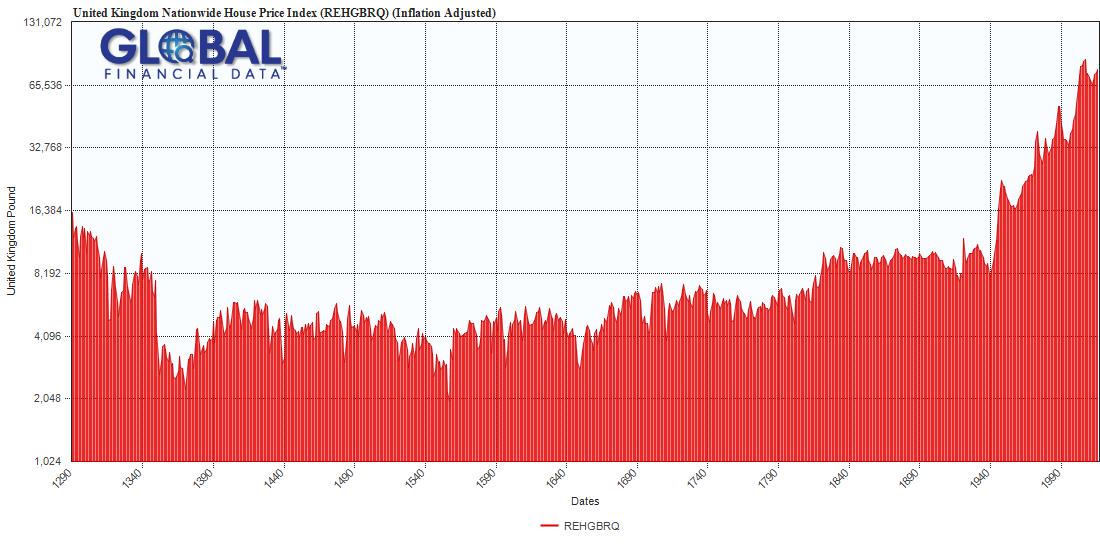

We are still amazed (horrified) by this graph, from the independent research firm Global Financial Data.

They point out that the cost of UK housing in 1940 was lower in real terms than it was in 1340. Since then, housing has become eight times more costly, again in real terms.

It seems pretty clear that something started going badly wrong over the second half of the twentieth century. What was it?

After the amazing 2017 YIMBY conference organized by East Bay Forward, many of our American friends have been asking about air rights.

Air rights or ‘Tradeable development rights’ (‘TDRs’) are used in New York and in some 22 other states.¹

Zoning systems with TDRs set two limits for each property – the ordinary zoning envelope and a higher envelope that can be reached if the landowner buys from other property owners their space under the zoning envelope. Professor David Schleicher of Yale has suggested the envelope can be seen as a ‘budget’, or the overall allowable amount of building.

Schleicher notes that TDRs are often used to subsidize certain land uses like New York’s ‘theaters’.

In New York, TDRs can normally only be used by another landowner on the same block, but Schleicher suggests that they could be tradeable citywide.

Subject to state constitutional requirements, one way to overcome electoral obstacles to more housing could be to propose a reform that allocates TDRs to every registered voter (including tenants and people who are homeless, not just landowners) on the date of the reform. Those TDRs would have a financial value and each voter could choose to sell them when they wanted.

The use (not the initial allocation) of the TDRs could be limited to certain areas of the city – near transit for example – to make their use less controversial and keep development away from the neighbourhoods that are historic or most resistant to change.

Basically the reform would hand every voter a valuable right that they could sell when they want to, while guiding new development to the right areas. We think it could be a powerful way to win majority support for reform in US cities with fewer objections to tall buildings and fewer historic buildings to protect.

Please get in touch if you'd like to know more!

1. Much of this description is adapted from Schleicher, David and Hills, Jr., Roderick M., Planning an Affordable City (November 13, 2015). Iowa Law Review, Vol. 101, pp. 91-136, 2015; Yale Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 558; Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 530. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2690311

More homes will make our streets better if we build them well.

Ending the housing crisis will make society much fairer. If done well, it will also make our cities, towns and villages better, improve the environment, and boost economic growth by an extra 2% a year for 15 years, creating many great jobs and opportunities.

We would like to see these ideas in party manifestos:

Any of these could create millions more homes over time, while making nearly everyone better off. Which parties will show they are most serious about ending the housing crisis?

Many say road pricing is a good idea because it means people only use roads when they need to. That reduces congestion, encourages ride sharing, cycling, walking and buses, and increases road capacity for important journeys. More road capacity would unlock a lot more housing, which is why we’re interested.

Economists think road pricing (varying with time and demand) is much better than a congestion charge or a free-for-all. The problem is that bringing in road pricing would make some people worse off – particularly some poorer people.

Is there a win-win solution? Building on ideas of Prof. Lee Anne Fennell from the University of Chicago, we think there could be.

Win-win solutions are the Holy Grail of politics. If you make everyone better off, only those who really want to see other people lose will be unhappy.

Economists call win-win solutions ‘Pareto superior’. Having invented that phrase, they almost never use it in real life. Most economists and governments look for reforms that are just ‘Kaldor-Hicks’ improvements: they could be win-win solutions, if you went round afterwards and redistributed some of the winnings to the losers. But no-one ever does that redistribution, so all the potential losers fight tooth and nail to prevent the reform. Special interest groups have many ways to block reform, as the late Mancur Olson explained. That’s a big reason why many otherwise good reforms don’t happen.

Almost by definition, when an economist thinks something works badly, it’s because there are win-win ways to improve it. The devil, of course, is in the details.

Why don’t people suggest true win-win refoms? Sometimes they have an agenda (subconscious or not) to help one group over another. Often, we suspect, the answer is because it’s very fiddly. Economists don’t like fiddly details, and lawyers who are supposed to deal with fiddly details often don’t like economics.

We think that means many good reforms die for lack of thinking through the political realities and the art of the possible.

How do we apply this to road pricing? Why not let each person set their own level of compensation for which they’d be willing to move to a given system of road pricing with lower (or zero) road and fuel taxes? That is – the price that they would pay the government to be allowed to switch if they think it would save them money, or the price that they would want from the government if they think the switch would cost them money.

Then the government can decide when and which people to switch over, as time goes by. Some people might demand high prices to switch, but the government hasn’t guaranteed that it will always pay the price people have asked. The government can always wait until only a small minority hasn’t been switched over, and then just pay each remaining person what the government believes to be fair based on objective principles (that it could set out in advance). It’s like a reverse auction. And if everyone’s price is too high, the government doesn’t have to do anything.

That way, most people will know they are very likely to be better off after the reform, because they know the vast majority of people will only be switched if they receive the price they want. They also have good reason to set a fair price for themselves so that they don't have a price imposed on them at the end.

That sort of idea would never have been possible without modern technology. But now we have it, why don’t we try it – in a particular city, for example?

We recently went to a disastrous local planning workshop.

Why was it so bad?

First, it was during the working day, for the convenience of the professionals. That meant the community participants were massively skewed to those who were anti-change and anti-growth. Hint: those who are most pro-homes and pro-growth often find it hard to clear a weekday morning at short notice. They often find email easier than meetings. They like preparation, not patronizing exercises with felt-tip pens.

Second, the plan was incredibly general, about use of sites. Because none of the community members knew what the resulting new buildings would look like, they felt the safest thing was to oppose all change. It is much easier to get people to support change with specific proposals for attractive designs. Asking people to write blank cheques is the hardest possible way.

Third, there were no specific proposals for any community benefit, in a part of London with high poverty rates but high commercial rents. It would be very easy to improve the lives of many for very little cost, given the economic potential at stake. Yet there was no effort to do that.

Fourth, the professionals had already been briefed, but the community representatives were surprised by various pieces of news during the session, giving them no time to consult with their communities. Again, the safest reaction was to err on the side of caution.

It almost seemed like the authority involved was bending over backwards to get as much opposition as possible.

Except that it wasn't: it was trying to be pro-growth. It had just failed to do anything to let that happen, and done a host of things to stop it.

We can all do so much better than this. If you're a local authority who wants more homes and more growth, we're happy to help for free. Please get in touch.

We could have many more of these if we got our act together

Why does some land sit being used less than it could be, when there is such a shortage of housing and space for businesses?

We are not talking about housebuilders, which we have covered elsewhere. That is a complicated and different question.

There are some plots of land in existing towns and cities that lie derelict or with dilapidated buildings that the community would love to see replaced or upgraded. Opinions differ about how many, but there are at least a few. That land is often owned by families or by investment companies. How can this make sense? Are they crazy?

Sitting on land can make sense if you think you will make more money by doing that than by building homes on it now. House prices have rocketed ever since the the 1940s, after 500 years of little change, so there are some good reasons to think that.

700 years of UK house prices adjusted for inflation, from Global Financial Data

Of course, they are losing out on rents that they could receive. They could develop the land and lease it out, like the great estates used to do, but after the leasehold reforms that means they would lose control of many aspects of it forever.

Couldn't they sell the land to someone to develop and buy another asset to sit on? They could, but that might incur capital gains tax. They have often owned the land for a long time.

They might also like the lack of clarity about the current value (due to lack of planning permission) but high potential end value, to keep inheritance taxes down in the meantime. They might have historical connections to that piece of land and to the local government who will make decisions about it, which makes that land more valuable to them than to a potential buyer.

The owners may not have the funds to pay for the development, and not want to borrow it or lose control by teaming up with someone else. Some people just like having an asset that goes up in value by, say, five or six percent a year forever. It has a lot of what economists call real option value – the freedom to choose later from a range of possible things to do with it.

What's more, they will know that the number of homes they will get permission to build on the land will probably increase over time, as the housing crisis gets worse. Building homes on it now would make it impossible to add more homes later, because the current system gives massive weight to the views of existing residents (but not so much weight that existing residents are happy about new development, as the frequent waves of protest show).

We've written about potential sensible property tax reforms here, but the idea we wrote about would only take effect after the next transfer of the land, which wouldn't help here. We'd love to hear any politically feasible plans for tax reforms to fix this sort of situation, if you have one.

If we can't fix that, the easiest thing to change is the expectation that prices will keep going up. After all, they stayed nearly flat for 500 years until the 1940s. That will create a race to use derelict plots now before prices drop. The easiest way to do that is to make sure that many more beautiful, decent, secure homes get built. That will end the housing crisis and make our existing places better. We've written about a suggestion for that here. Please let us have your thoughts and other ideas.

Grassroots campaign to end the housing crisis with the support of local people

Powered by Squarespace.